ESA’s Euclid celebrates first science with sparkling cosmic views

ESA’s Euclid space mission released five unprecedented new views of the Universe. The never-before-seen images demonstrate Euclid’s ability to unravel the secrets of the cosmos and enable scientists to hunt for rogue planets, use lensed galaxies to study mysterious matter, and explore the evolution of the Universe.

The new images are part of Euclid’s Early Release Observations. They accompany the mission’s first scientific data, also made public today, and 10 forthcoming science papers. The treasure trove comes less than a year after the space telescope’s launch, and roughly six months after it returned its first full-colour images of the cosmos.

The full set of early observations targeted 17 astronomical objects, from nearby clouds of gas and dust to distant clusters of galaxies, ahead of Euclid’s main survey. This survey aims to uncover the secrets of the dark cosmos and reveal how and why the Universe looks as it does today.

The Institute of Space Science – A Subsidiary of INFLPR is an active member of the Euclid Consortium.

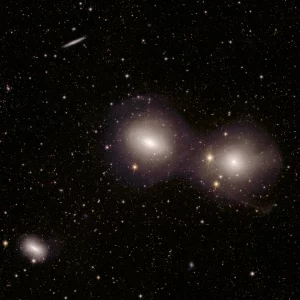

Euclid’s new image of the Dorado group of galaxies

The Dorado Group of galaxies is one of the richest galaxy groups in the southern hemisphere. Here, Euclid captures signs of galaxies evolving and merging ‘in action’, with beautiful tidal tails and shells visible as a result of ongoing interactions. As Dorado is a lot younger than other clusters (like Fornax), several of its constituent galaxies are still forming stars and remain in the stage of interacting with one another, while others show signs of having merged relatively recently. In size, it sits between larger galaxy clusters and smaller galaxy groups, making it a useful and fascinating object to study with Euclid.

This dataset is enabling scientists to study how galaxies evolve and collide over time in order to improve our models of cosmic history and understand how galaxies form within halos of dark matter, with this new image being a true testament to Euclid’s immense versatility. A wide array of galaxies is visible here, from very bright to very faint. Thanks to Euclid’s unique combination of large field-of-view and high spatial resolution, for the first time we can use the same instrument and observations to deeply study tiny (small objects the size of star clusters), wider (the central parts of a galaxy) and extended (tidal merger tails) features over a large part of the sky.

Scientists are also using Euclid observations of the Dorado Group to answer questions that previously could only be explored using painstakingly small snippets of data. This includes compiling a full list of the individual clusters of stars (globular clusters) around the galaxies seen here. Once we know where these clusters are, we can use them to trace how the galaxies formed and study their history and contents. Scientists will also use these data to hunt for new dwarf galaxies around the Group, as it did previously with the Perseus cluster.

The Dorado Group lies 62 million light-years away in the constellation of Dorado.

Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.

Euclid’s new image of star-forming region Messier 78

This breathtaking image features Messier 78 (the central and brightest region), a vibrant nursery of star formation enveloped in a shroud of interstellar dust. This image is unprecedented – it is the first shot of this young star-forming region at this width and depth.

Euclid peered deep into this enshrouded nursery using its infrared camera, exposing hidden regions of star formation for the first time, mapping its complex filaments of gas and dust in unprecedented detail, and uncovering newly formed stars and planets. This is the first time we’ve been able to see these smaller, sub-stellar sized objects in Messier 78; the dark clouds of gas and dust usually hide them from view, but Euclid’s infrared ‘eyes’ can see through these obscuring clouds to explore within.

Euclid’s sensitive instruments can detect objects just a few times the mass of Jupiter, and its visible and infrared instruments – the VIS and NISP cameras – reveal over 300 000 new objects in this field of view alone. Scientists are using this data to study the amount and ratio of stars and sub-stellar objects here, which is key to understanding the dynamics of how star populations form and change over time. Sub-stellar objects like brown dwarfs and free-floating or ‘rogue’ planets are also one possible candidate for dark matter. While our current knowledge suggests that there aren’t enough of these objects to solve the mystery of dark matter in the Milky Way, it remains an open question, and one that Euclid will definitively answer by probing a significant fraction of our galaxy.

Also visible to the top of the frame is the bright nebula NGC 2071, and a third filament of star formation towards the bottom of the image (with a ‘traffic light’-like appearance). This lower region is a dark nebula producing lower-mass stars, all arranged along elongated filaments in space.

Messier 78 lies 1300 light-years away in the constellation of Orion.

Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.

Euclid’s new image of spiral galaxy NGC 6744

Here, Euclid captures NGC 6744, one of the largest spiral galaxies beyond our local patch of space. It’s a typical example of the type of galaxy currently forming most of the stars in the nearby Universe, making it a wonderful archetype to study with Euclid.

Euclid’s large field-of-view covers the entire galaxy, revealing not only spiral structure on larger scales but also capturing exquisite detail on small spatial scales, and at a combination of wavelengths. This detail includes feather-like lanes of dust emerging as ‘spurs’ from the spiral arms, which Euclid is able to image with incredible clarity. Euclid’s observations will allow scientists to not only count individual stars within NGC 6744 but also trace the wider distribution of stars and dust in the galaxy, as well as mapping the dust associated with the gas that fuels new star formation. Forming stars is the main way by which galaxies grow and evolve, so these investigations are central to understanding galaxy evolution – and why our Universe looks the way it does today.

Euclid scientists are using this dataset to understand how dust and gas are linked to star formation; map how different stellar populations are distributed throughout galaxies and where stars are currently forming; and unravel the physics behind the structure of spiral galaxies, something that’s still not fully understood after decades of study. Spiral structure is important in galaxies, as spiral arms move and compress gas to foster star formation (most of which occurs along these arms). However, the exact role of spirals in coordinating ongoing star formation remains unclear. As the aforementioned ‘spurs’ along NGC 6744’s arms are only able to form in a strong enough spiral, these features therefore provide important clues as to why galaxies look and behave as they do.

The dataset will also allow scientists to identify clusters of old stars (globular clusters) and hunt for new dwarf galaxies around NGC 6744. In fact, Euclid has already found a new dwarf ‘satellite galaxy’ of NGC 6744 – a surprise given that this galaxy has been intensively studied in the past.

NGC 6744 lies 30 million light-years away within the Local Group.

Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.

Euclid’s new view of galaxy cluster Abell 2764

This new view shows the galaxy cluster Abell 2764 (top right), a very dense region of space containing hundreds of galaxies orbiting within a halo of dark matter.

Euclid captures a range of objects in this patch of sky, including many background galaxies, more distant galaxy clusters, interacting galaxies that have thrown off streams and shells of stars, and a pretty edge-on spiral that allows us to see the ‘thinness’ of its disk.

This complete view of Abell 2764 and surroundings – obtained thanks to Euclid’s impressively wide field-of-view – allows scientists to ascertain the radius of the cluster and study its outskirts with faraway galaxies still in frame. Euclid’s observations of Abell 2764, as with Abell 2390 (another target depicted in the images released today from the space telescope), are also allowing scientists to witness some of the most distant galaxies that lived in a mysterious period known as the cosmic dark ages. Euclid enables us to see these galaxies back when the Universe was only 700 million years old, just 5% of its current age. Viewing their light is a specialty of Euclid, and allows us to witness how the first galaxies formed.

Also seen here is a bright foreground star that lies within our own galaxy (lower left: this is Beta Phoenicis, a star within our galaxy and in the southern hemisphere that’s bright enough to be seen by the human eye). When we look at a star through a telescope, its light is scattered outwards into the typical spiked shape due to the telescope’s optics. Euclid was designed to make this scatter as small as possible. As a result, we can measure the star very accurately, and capture galaxies that lie nearby without being blinded by the star’s brightness.

Abell 2764 lies 3.5 billion light-years away in the direction of the Phoenix constellation.

Credit: ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA, image processing by J.-C. Cuillandre (CEA Paris-Saclay), G. Anselmi; CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO or ESA Standard Licence.

Full resolution pictures as well as various zoomed images and further information may be found at https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Euclid.

Contact: vpopa@spacescience.ro